Other News

3 Former Packers Legends Causing a Stir: Do They Deserve a Spot in the Hall of Fame?

Sterling Sharpe’s induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame caps off several decades of work by Packers fans. Thanks to the tireless advocacy of fans and those covering the team, Sharpe has finally made the leap into Canton, joining his brother, Shannon, among the football immortals. His induction marks the third time in recent years that a Packers player finally made the cut after a long wait, along with Jerry Kramer and LeRoy Butler.

Sharpe, Kramer, and Butler may be the three most obvious omissions in the Hall of Fame, but they’re not the only ones. Here are a few more players from the history books who deserve another shot at football immortality.

Verne Lewellen (1924-1932)

Lewellen is far from a household name. There’s a good chance your grandparents weren’t even alive to see him play. But he’s almost certainly the best Packers player not in the Hall of Fame — and he might be the best player of any team not to receive that honor.

Lewellen starred on offense and defense for the Curly Lambeau-era Packers, playing a crucial role on the Packers 1929-31 championship three-peat. He was so good that, when picking his all-time team, Lambeau regarded Llewellen as one of the best players he ever coached, naming him to his all-time team ahead of other Packers greats like Johnny Blood, Arnie Herber, and Tony Canadeo.

And get this — Blood, never lacking in ego or bravado, agreed with this coach. Here’s how official team historian Cliff Christl paints the picture:

When Curly Lambeau picked his all-time Packers team after the 1948 season, which was his second-to-last as their coach, his two halfbacks were Lewellen and Cecil Isbell over Pro Football Hall of Famers Johnny Blood, Arnie Herber and Tony Canadeo, who was seven years into his 11-year career. Lambeau chose Red Dunn as his quarterback and Clarke Hinkle as his fullback. In 1957, George Whitney Calhoun, the Packers’ co-founder, picked the same backfield on his all-time team. In his case, he had seen almost every home Packers game for 38 years and almost all of their road games for more than 25 of those years.

When Blood was inducted in Canton as a charter member, he said, “Verne Lewellen should have been in there in front of me and (Cal) Hubbard.”

What sets Lewellen apart? He led the league in touchdowns during his career, the only official stat we have from his era, but his real forte might have been his punting. In a different era of football, when punting was a much more central part of down-to-down gameplay than it is today, Lewellen was a weapon for the Packers, routinely pinning teams deep in their own territory and far against the sideline.

Lewellen did it all, and did it all well. If we’re going to routinely have arguments about who the “GOAT” is, the Pro Football Hall of Fame should at least acknowledge one of the greats from the league’s most distant past.

Bob Skoronski (1956-1968)

Skoronski doesn’t have the bona fides that Lewellen did. Though he was a part of all five championships of the Lombardi era, he only made the Pro Bowl once in his career, and he was never an All-Pro.

What does he have, then? Votes of confidence from two of the biggest names in football history: Vince Lombardi and Bart Starr.

When he needed a leader, Lombardi didn’t turn to Starr or all-world lineman Forrest Gregg. No, he turned to Skoronski, who served as the offense’s permanent captain from 1964-68, playing a crucial role during the Packers’ championship three-peat from 1965-67.

And Starr said Lombardi was right to do so. Stumping for Skoronski in the early 2000s, Starr said “If you checked his blocking grades each week, they were just a fraction under Forrest [Gregg].

Then, a little more than a decade ago, Starr made an impassioned case for Skoronski, saying “I just hope more and more people get on the backs of those who are at the Hall of Fame and say ‘Look, you need this guy in here.’”

(As an aside, how cool is it to hear and see a vibrant, healthy Bart Starr? What a gem of a person.)

If Lombardi and Starr think that highly of Skoronski, that’s good enough for me. Will it ever be enough for Hall of Fame voters? Probably not, but it’s at least worth remembering what his contemporaries thought of him.

Bill Forester (1953-1963)

Forester’s case is also challenging to establish, but he deserves a look. Though he was a three-time All-Pro during the Lombardi era, Forester was making plays in Green Bay before Lombardi ever arrived. From 1955-57, Forester intercepted twelve passes and recovered five fumbles, accounting for 17 turnovers in just 36 games. Had the Packers been anything but putrid during those years, Forester would have probably garnered more of the national attention that finally arrived during the Lombardi era and the success it brought.

Forester was a member of two championship teams under Lombardi, but his lasting impact in Green Bay extended beyond his playing days thanks to his tutelage of a young up-and-comer named Dave Robinson.

I spoke with Robinson a couple of years ago and he credited Forester with helping him to transition not just to the NFL, but to a new position. Robinson played defensive end in college but became a linebacker under Lombardi, and Forester showed him the ropes by holding after-hours study sessions during training camp in Robinson’s rookie year.

“Every night, if you were caught outside of your room after 11 o’clock curfew, it’s an automatic $500 fine, which is not that big today, but it was in those days. In the hall where we stayed [in training camp], the veterans were on the first floor and all the rookies had to sleep on the second floor. So, after 11 o’clock, I’d sneak down the back steps and go into Bill’s room, and he would go over the defense that we were going over in practice. See, there’s a difference between just the Xs and Os, and where to go, and where not to go. But why do you do this and why do you do that, and what can you expect from this guy, and what can you expect for that guy, and what do you think they’re going to do you? There’s a lot more to linebacker than just taking up, getting a playbook, and playing the play. And that’s the things he taught me.”

Forester wasn’t just a high-caliber player, he helped others reach their full potential, too. That sort of effort may not carry weight with Hall of Fame voters, but maybe it should.

Posts in same category:

-

D.K. Metcalf trade rumors hover over another Chiefs offseason in 2025…

-

Why Should the Packers Trade Jaire Alexander Instead of Release Him? – Here’s Why (WATCH VIDEO)

-

SAD NEWS: NFL Fans Are Praying For Patrick Mahomes’ Family After Devastating News

-

Dallas Cowboys To Draft Oregon Ducks Running Back Jordan James?

-

The 49ers intend to find a replacement for Trent Williams in the 2025 NFL Draft. Trent Williams’ reaction…

-

Mahomes Gives Brutal 3-Word Answer On Chiefs’ Super Bowl Narrative

-

Exclusive Insight: 3 Strategic Trades the Cowboys Could Make Without Touching Their Premium Draft Picks

-

Saquon Barkley: The Toughest Obstacle Standing in the Way of the Chiefs’ Quest for a Three-Peat vs Eagles!

-

The Shocking Truth: Micah Parsons Reveals Giants Lied to Him During the Draft!

-

The 49ers Should Look to Cam Skattebo as the Future Replacement for Kyle Juszczyk

-

VIDEO: The “Script” For Super Bowl 59 Was Leaked 7 Years Ago On Facebook, And No One Could Have Seen This Coming

-

Pittsburgh Steelers projected to draft highly-touted Texas wide receiver

-

Mike Tomlin Provides Update on Ryan Watts’ Surgery After Frightening Injury

-

Steelers Coach Mike Tomlin Makes It Clear That He Does Not Want To Be Traded

-

Steelers’ Justin Fields gets major endorsement from Mike Tomlin despite benching

-

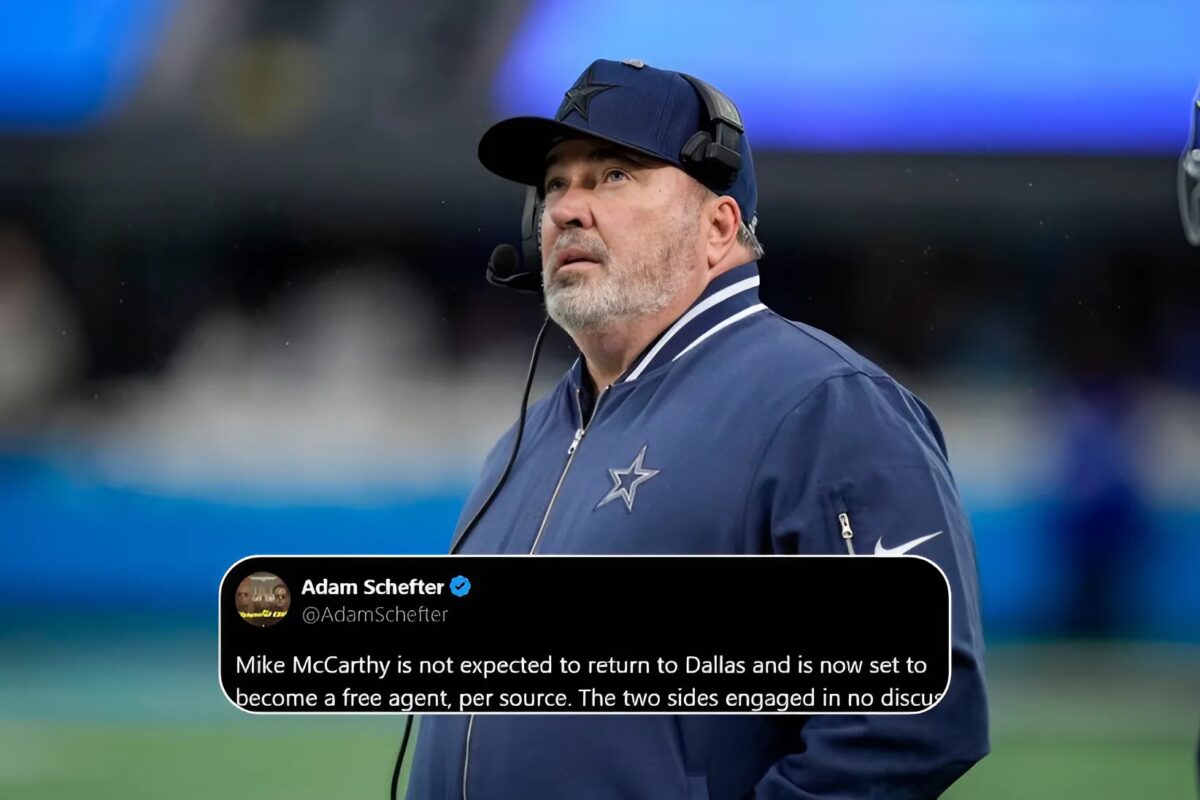

Mike McCarthy will not coach another game in Dallas